Colorectal Cancer Treatment

What is the pathophysiology of cancer?

What is colorectal cancer?

Colorectal cancer starts in the colon or the rectum. These cancers can also be called colon cancer or rectal cancer, depending on where they start. Colon cancer and rectal cancer are often grouped together because they have many features in common.

Colorectal cancer may be benign, or non-cancerous, or malignant. A malignant cancer can spread to other parts of the body and damage them.

About Iranian Surgery

About Iranian Surgery

Iranian surgery is an online medical tourism platform where you can find the best Surgeons to treat your colorectal cancer in Iran. The price of treating a colorectal cancer in Iran can vary according to each individual’s case and will be determined by the type of treatment you have and an in-person assessment with the doctor. So if you are looking for the cost of colorectal cancer treatment in Iran, you can contact us and get free consultation from Iranian surgery.

Read more about : Metastatic myxofibrosarcoma treatment with the best Iranian oncologist surgeon

Before Colorectal Cancer Treatment

The colon and rectum

To understand colorectal cancer, it helps to know about the normal structure and function of the colon and rectum.

The colon and rectum make up the large intestine (or large bowel), which is part of the digestive system, also called the gastrointestinal (GI) system (see illustration below).

Most of the large intestine is made up of the colon, a muscular tube about 5 feet (1.5 meters) long. The parts of the colon are named by which way the food is traveling through them.

. The first section is called the ascending colon. It starts with a pouch called the cecum, where undigested food is comes in from the small intestine. It continues upward on the right side of the abdomen (belly).

. The second section is called the transverse colon. It goes across the body from the right to the left side.

. The third section is called the descending colon because it descends (travels down) on the left side.

. The fourth section is called the sigmoid colon because of its “S” shape. The sigmoid colon joins the rectum, which then connects to the anus.

The ascending and transverse sections together are called the proximal colon. The descending and sigmoid colon are called the distal colon.

How do the colon and rectum work?

The colon absorbs water and salt from the remaining food matter after it goes through the small intestine (small bowel). The waste matter that's left after going through the colon goes into the rectum, the final 6 inches (15cm) of the digestive system. It's stored there until it passes through the anus. Ring-shaped muscles (also called a sphincter) around the anus keep stool from coming out until they relax during a bowel movement.

Read more about: Colorectal Cancer Recovery

How does colorectal cancer start?

Polyps in the colon or rectum

Most colorectal cancers start as a growth on the inner lining of the colon or rectum. These growths are called polyps.

Some types of polyps can change into cancer over time (usually many years), but not all polyps become cancer. The chance of a polyp turning into cancer depends on the type of polyp it is. There are different types of polyps.

. Adenomatous polyps (adenomas): These polyps sometimes change into cancer. Because of this, adenomas are called a pre-cancerous condition. The 3 types of adenomas are tubular, villous, and tubulovillous.

. Hyperplastic polyps and inflammatory polyps: These polyps are more common, but in general they are not pre-cancerous. Some people with large (more than 1cm) hyperplastic polyps might need colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy more often.

. Sessile serrated polyps (SSP) and traditional serrated adenomas (TSA): These polyps are often treated like adenomas because they have a higher risk of colorectal cancer.

Other factors that can make a polyp more likely to contain cancer or increase someone’s risk of developing colorectal cancer include:

. If a polyp larger than 1 cm is found

. If more than 3 polyps are found

. If dysplasia is seen in the polyp after it's removed. Dysplasia is another pre-cancerous condition. It means there's an area in a polyp or in the lining of the colon or rectum where the cells look abnormal, but they haven't become cancer.

Symptoms

Symptoms of colorectal cancer include:

. Changes in bowel habits

. Diarrhea or constipation

. A feeling that the bowel does not empty properly after a bowel movement

. Blood in feces that makes stools look black

. Bright red blood coming from the rectum

. Pain and bloating in the abdomen

. A feeling of fullness in the abdomen, even after not eating for a while.

. Fatigue or tiredness

. Unexplained weight loss

. A lump in the abdomen or the back passage felt by your doctor

. Unexplained iron deficiency in men, or in women after menopause

Most of these symptoms may also indicate other possible conditions. It is important to see a doctor if symptoms persist for 4 weeks or more.

Read more about: How you can Prevented from Colorectal Cancer?

Causes

What causes colorectal cancer?

Researchers are still studying the causes of colorectal cancer.

Cancer may be caused by genetic mutations, either inherited or acquired. These mutations don’t guarantee you’ll develop colorectal cancer, but they do increase your chances.

Some mutations may cause abnormal cells to accumulate in the lining of the colon, forming polyps. These are small, benign growths.

Removing these growths through surgery can be a preventive measure. Untreated polyps can become cancerous.

Who’s at risk for colorectal cancer?

There’s a growing list of risk factors that act alone or in combination to increase a person’s chances of developing colorectal cancer.

. Fixed risk factors

Some factors that increase your risk of developing colorectal cancer are unavoidable and can’t be changed. Age is one of them. Your chances of developing this cancer increase after you reach the age of 50.

Some other fixed risk factors are:

. A prior history of colon polyps

. A prior history of bowel diseases

. A family history of colorectal cancer

. Having certain genetic syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

. Being of Eastern European Jewish or African descent

. Modifiable risk factors

Other risk factors are avoidable. This means you can change them to decrease your risk of developing colorectal cancer. Avoidable risk factors include:

. Being overweight or having obesity

. Being a smoker

. Being a heavy drinker

. Having type 2 diabetes

. Having a sedentary lifestyle

. Consuming a diet high in processed meats

Diagnosis

Screening can detect polyps before they become cancerous, as well as detecting colon cancer during its early stages when the chances of a cure are much higher.

The following are the most common screening and diagnostic procedures for colorectal cancer.

. Fecal occult blood test (blood stool test)

This checks a sample of the patient’s stool (feces) for the presence of blood. This can be done at the doctor’s office or with a kit at home. The sample is returned to the doctor’s office, and it is sent to a laboratory.

A blood stool test is not 100-percent accurate, because not all cancers cause a loss of blood, or they may not bleed all the time. Therefore, this test can give a false negative result. Blood may also be present because of other illnesses or conditions, such as hemorrhoids. Some foods may suggest blood in the colon, when in fact, none was present.

. Stool DNA test

This test analyzes several DNA markers that colon cancers or precancerous polyps cells shed into the stool. Patients may be given a kit with instructions on how to collect a stool sample at home. This has to be brought back to the doctor’s office. It is then sent to a laboratory.

This test is more accurate for detecting colon cancer than polyps, but it cannot detect all DNA mutations that indicate that a tumor is present.

. Flexible sigmoidoscopy

The doctor uses a sigmoidoscope, a flexible, slender and lighted tube, to examine the patient’s rectum and sigmoid. The sigmoid colon is the last part of the colon, before the rectum.

The test takes a few minutes and is not painful, but it might be uncomfortable. There is a small risk of perforation of the colon wall.

If the doctor detects polyps or colon cancer, a colonoscopy can then be used to examine the entire colon and take out any polyps that are present. These will be examined under a microscope.

A sigmoidoscopy will only detect polyps or cancer in the end third of the colon and the rectum. It will not detect a problem in any other part of the digestive tract.

. Barium enema X-ray

Barium is a contrast dye that is placed into the patient’s bowel in an enema form, and it shows up on an X-ray. In a double-contrast barium enema, air is added as well.

The barium fills and coats the lining of the bowel, creating a clear image of the rectum, colon, and occasionally of a small part of the patient’s small intestine.

A flexible sigmoidoscopy may be done to detect any small polyps the barium enema X-ray may miss. If the barium enema X-ray detects anything abnormal, the doctor may recommend a colonoscopy.

. Colonoscopy

A colonoscope is longer than a sigmoidoscope. It is a long, flexible, slender tube, attached to a video camera and monitor. The doctor can see the whole of the colon and rectum. Any polyps discovered during this exam can be removed during the procedure, and sometimes tissue samples, or biopsies, are taken instead.

A colonoscopy is painless, but some patients are given a mild sedative to calm them down. Before the exam, they may be given laxative fluid to clean out the colon. An enema is rarely used. Bleeding and perforation of the colon wall are possible complications, but extremely rare.

. CT colonography

A CT machine takes images of the colon, after clearing the colon. If anything abnormal is detected, conventional colonoscopy may be necessary. This procedure may offer patients at increased risk of colorectal cancer an alternative to colonoscopy that is less-invasive, better-tolerated, and with good diagnostic accuracy.

. Imaging scans

Ultrasound or MRI scans can help show if the cancer has spread to another part of the body.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend regular screening for those aged 50 to 75 years. The frequency depends on the type of test.

Prevention

A number of lifestyle measures may reduce the risk of developing colorectal cancer:

. Regular screenings: People who have had colorectal cancer before, who are over 50 years of age, who have a family history of this type of cancer, or who have Crohn’s disease, Lynch syndrome, or adenomatous polyposis should have regular screenings.

. Nutrition: Follow a diet with plenty of fiber, fruit, vegetables, and good quality carbohydrates and a minimum of red and processed meats. Switch from saturated fats to good quality fats, such as avocado, olive oil, fish oils, and nuts.

. Exercise: Moderate, regular exercise has been shown to have a significant impact on lowering a person’s risk of developing colorectal cancer.

. Bodyweight: Being overweight or obese raises the risk of many cancers, including colorectal cancer.

A study published in the journal Cell has suggested that aspirin could be effective in boosting the immune system in patients suffering from breast, skin and bowel cancer.

A gene linked to bowel cancer recurrence and shortened survival could help predict outcomes for patients with the gene – and take scientists a step closer to development of personalized treatments, reveals research in the journal Gut.

A study published in Science found that 300 oranges’ worth of vitamin C impairs cancer cells, suggesting that the power of vitamin C could one day be harnessed to fight colorectal cancer.

Researchers have found that drinking coffee every day – even decaffeinated coffee – may lower the risk of colorectal cancer.

How colorectal cancer spreads

If cancer forms in a polyp, it can grow into the wall of the colon or rectum over time. The wall of the colon and rectum is made up of many layers. Colorectal cancer starts in the innermost layer (the mucosa) and can grow outward through some or all of the other layers.

When cancer cells are in the wall, they can then grow into blood vessels or lymph vessels (tiny channels that carry away waste and fluid). From there, they can travel to nearby lymph nodes or to distant parts of the body.

The stage (extent of spread) of a colorectal cancer depends on how deeply it grows into the wall and if it has spread outside the colon or rectum.

During Colorectal Cancer Treatment

Types of cancer in the colon and rectum

Most colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas. These cancers start in cells that make mucus to lubricate the inside of the colon and rectum. When doctors talk about colorectal cancer, they're almost always talking about this type. Some sub-types of adenocarcinoma, such as signet ring and mucinous, may have a worse prognosis (outlook) than other subtypes of adenocarcinoma.

Other, much less common types of tumors can also start in the colon and rectum. These include:

. Carcinoid tumors. These start from special hormone-making cells in the intestine.

. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) start from special cells in the wall of the colon called the interstitial cells of Cajal. Some are benign (not cancer). These tumors can be found anywhere in the digestive tract, but are not common in the colon.

. Lymphomas are cancers of immune system cells. They mostly start in lymph nodes, but they can also start in the colon, rectum, or other organs. Information on lymphomas of the digestive system can be found in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

. Sarcomas can start in blood vessels, muscle layers, or other connective tissues in the wall of the colon and rectum. Sarcomas of the colon or rectum are rare.

Treatment

What are the treatment options for colorectal cancer?

Treatment of colorectal cancer depends on a variety of factors. The state of your overall health and the stage of your colorectal cancer will help your doctor create a treatment plan.

. Surgery

In the earliest stages of colorectal cancer, it might be possible for your surgeon to remove cancerous polyps through surgery. If the polyp hasn’t attached to the wall of the bowels, you’ll likely have an excellent outlook.

If your cancer has spread into your bowel walls, your surgeon may need to remove a portion of the colon or rectum along with any neighboring lymph nodes. If at all possible, your surgeon will reattach the remaining healthy portion of the colon to the rectum.

If this isn’t possible, they may perform a colostomy. This involves creating an opening in the abdominal wall for the removal of waste. A colostomy may be temporary or permanent.

. Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy involves the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. For people with colorectal cancer, chemotherapy commonly takes place after surgery, when it’s used to destroy any lingering cancerous cells. Chemotherapy also controls the growth of tumors.

Chemotherapy drugs used to treat colorectal cancer include:

. Capecitabine (Xeloda)

. Fluorouracil

. Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin)

. Irinotecan (Camptosar)

Chemotherapy often comes with side effects that need to be controlled with additional medication.

. Radiation

Radiation uses a powerful beam of energy, similar to that used in X-rays, to target and destroy cancerous cells before and after surgery. Radiation therapy commonly occurs alongside chemotherapy.

. Ablation

Ablation can destroy a tumor without removing it. It can be carried out using radiofrequency, ethanol, or cryosurgery. These are delivered using a probe or needle that is guided by ultrasound or CT scanning technology.

. Other medications

Targeted therapies and immunotherapies may also be recommended. Drugs that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat colorectal cancer include:

. Bevacizumab (Avastin)

. Ramucirumab (Cyramza)

. Ziv-aflibercept (Zaltrap)

. Cetuximab (Erbitux)

. Panitumumab (Vectibix)

. Regorafenib (Stivarga)

. Pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

. Nivolumab (Opdivo)

. Ipilimumab (Yervoy)

They can treat metastatic, or late-stage, colorectal cancer that doesn’t respond to other types of treatment and has spread to other parts of the body.

Treatment of Colon Cancer, by Stage

Treatment for colon cancer is based largely on the stage (extent) of the cancer, but other factors can also be important.

People with colon cancers that have not spread to distant sites usually have surgery as the main or first treatment. Chemotherapy may also be used after surgery (called adjuvant treatment). Most adjuvant treatment is given for about 6 months.

. Treating stage 0 colon cancer

Since stage 0 colon cancers have not grown beyond the inner lining of the colon, surgery to take out the cancer is often the only treatment needed. In most cases this can be done by removing the polyp or taking out the area with cancer through a colonoscope (local excision). Removing part of the colon (partial colectomy) may be needed if a cancer is too big to be removed by local excision.

. Treating stage I colon cancer

Stage I colon cancers have grown deeper into the layers of the colon wall, but they have not spread outside the colon wall itself or into the nearby lymph nodes.

Stage I includes cancers that were part of a polyp. If the polyp is removed completely during colonoscopy, with no cancer cells at the edges (margins) of the removed piece, no other treatment may be needed.

If the cancer in the polyp is high grade, or there are cancer cells at the edges of the polyp, more surgery might be recommended. You might also be advised to have more surgery if the polyp couldn’t be removed completely or if it had to be removed in many pieces, making it hard to see if cancer cells were at the edges.

For cancers not in a polyp, partial colectomy ─ surgery to remove the section of colon that has cancer and nearby lymph nodes ─ is the standard treatment. You typically won't need any more treatment.

. Treating stage II colon cancer

Many stage II colon cancers have grown through the wall of the colon, and maybe into nearby tissue, but they have not spread to the lymph nodes.

Surgery to remove the section of the colon containing the cancer (partial colectomy) along with nearby lymph nodes may be the only treatment needed. But your doctor may recommend adjuvant chemotherapy (chemo after surgery) if your cancer has a higher risk of coming back (recurring) because of certain factors, such as:

. The cancer looks very abnormal (is high grade) when viewed closely in the lab.

. The cancer has grown into nearby blood or lymph vessels.

. The surgeon did not remove at least 12 lymph nodes.

. Cancer was found in or near the margin (edge) of the removed tissue, meaning that some cancer may have been left behind.

. The cancer had blocked (obstructed) the colon.

. The cancer caused a perforation (hole) in the wall of the colon.

The doctor might also test your tumor for specific gene changes, called MSI or MMR, to help decide if adjuvant chemotherapy would be helpful.

Not all doctors agree on when chemo should be used for stage II colon cancers. It’s important for you to discuss the risks and benefits of chemo with your doctor, including how much it might reduce your risk of recurrence and what the likely side effects will be.

If chemo is used, the main options include 5-FU and leucovorin, oxaliplatin, or capecitabine, but other combinations may also be used.

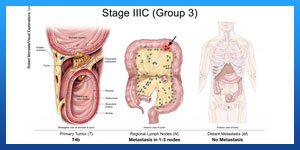

. Treating stage III colon cancer

Stage III colon cancers have spread to nearby lymph nodes, but they have not yet spread to other parts of the body.

Surgery to remove the section of the colon with the cancer (partial colectomy) along with nearby lymph nodes, followed by adjuvant chemo is the standard treatment for this stage.

For chemo, either the FOLFOX (5-FU, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) or CapeOx (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) regimens are used most often, but some patients may get 5-FU with leucovorin or capecitabine alone based on their age and health needs.

For some advanced colon cancers that cannot be removed completely by surgery, neoadjuvant chemotherapy given along with radiation (also called chemoradiation) might be recommended to shrink the cancer so it can be removed later with surgery. For some advanced cancers that have been removed by surgery, but were found to be attached to a nearby organ or have positive margins (some of the cancer may have been left behind), adjuvant radiation might be recommended. Radiation therapy and/or chemo may be options for people who aren’t healthy enough for surgery.

. Treating stage IV colon cancer

Stage IV colon cancers have spread from the colon to distant organs and tissues. Colon cancer most often spreads to the liver, but it can also spread to other places like the lungs, brain, peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity), or to distant lymph nodes.

In most cases surgery is unlikely to cure these cancers. But if there are only a few small areas of cancer spread (metastases) in the liver or lungs and they can be removed along with the colon cancer, surgery may help you live longer. This would mean having surgery to remove the section of the colon containing the cancer along with nearby lymph nodes, plus surgery to remove the areas of cancer spread. Chemo is typically given after surgery, as well. In some cases, hepatic artery infusion may be used if the cancer has spread to the liver.

If the metastases cannot be removed because they're too big or there are too many of them, chemo may be given before surgery (neoadjuvant chemo). Then, if the tumors shrink, surgery may be tried to remove them. Chemo might be given again after surgery. For tumors in the liver, another option may be to destroy them with ablation or embolization.

If the cancer has spread too much to try to cure it with surgery, chemo is the main treatment. Surgery might still be needed if the cancer is blocking the colon or is likely to do so. Sometimes, such surgery can be avoided by putting a stent (a hollow metal tube) into the colon during a colonoscopy to keep it open. Otherwise, operations such as a colectomy or diverting colostomy (cutting the colon above the level of the cancer and attaching the end to an opening in the skin on the belly to allow waste out) may be used.

If you have stage IV cancer and your doctor recommends surgery, it’s very important to understand the goal of the surgery ─ whether it's to try to cure the cancer or to prevent or relieve symptoms of the cancer.

Most people with stage IV cancer will get chemo and/or targeted therapies to control the cancer. Some of the most commonly used regimens include:

. FOLFOX: leucovorin, 5-FU, and oxaliplatin (Eloxatin)

. FOLFIRI: leucovorin, 5-FU, and irinotecan (Camptosar)

. CAPEOX or CAPOX: capecitabine (Xeloda) and oxaliplatin

. FOLFOXIRI: leucovorin, 5-FU, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan

. One of the above combinations plus either a drug that targets VEGF, (bevacizumab [Avastin], ziv-aflibercept [Zaltrap], or ramucirumab [Cyramza]), or a drug that targets EGFR (cetuximab [Erbitux] or panitumumab [Vectibix])

. 5-FU and leucovorin, with or without a targeted drug

. Capecitabine, with or without a targeted drug

. Irinotecan, with or without a targeted drug

. Cetuximab alone

. Panitumumab alone

. Regorafenib (Stivarga) alone

. Trifluridine and tipiracil (Lonsurf)

The choice of regimens depends on several factors, including any previous treatments you’ve had and your overall health.

If one of these regimens is no longer working, another may be tried. For people with certain tumor changes in the MMR genes, another option after initial chemotherapy might be treatment with an immunotherapy drug such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or nivolumab (Opdivo).

For advanced cancers, radiation therapy can also be used to help prevent or relieve symptoms in the colon from the cancer such as pain. It might also be used to treat areas of spread such as in the lungs or bone. It may shrink tumors for a time, but it's not likely to cure the cancer. If your doctor recommends radiation therapy, it’s important that you understand the goal of treatment.

Treating recurrent colon cancer

Recurrent cancer means that the cancer has come back after treatment. The recurrence may be local (near the area of the initial tumor), or it may be in distant organs.

. Local recurrence

If the cancer comes back locally, surgery (often followed by chemo) can sometimes help you live longer and may even cure you. If the cancer can’t be removed surgically, chemo might be tried first. If it shrinks the tumor enough, surgery might be an option. This might be followed by more chemo.

. Distant recurrence

If the cancer comes back in a distant site, it's most likely to appear in the liver first. Surgery might be an option for some people. If not, chemo may be tried to shrink the tumor(s), which may then be followed by surgery to remove them. Ablation or embolization techniques might also be an option to treat some liver tumors.

If the cancer has spread too much to be treated with surgery, chemo and/or targeted therapies may be used. Possible treatment schedules are the same as for stage IV disease.

For people whose cancers are found to have certain gene changes, another option might be treatment with immunotherapy.

Your options depend on which, if any, drugs you had before the cancer came back and how long ago you got them, as well as your overall health. You may still need surgery at some point to relieve or prevent blockage of the colon or other local problems. Radiation therapy may be an option to relieve symptoms as well.

Recurrent cancers can often be hard to treat, so you might also want to ask your doctor if clinical trials of newer treatments are available.

After Colorectal Cancer Treatment

Living as a Colorectal Cancer Survivor

For many people with colorectal cancer, treatment can remove or destroy the cancer. The end of treatment can be both stressful and exciting. You may be relieved to finish treatment, but find it hard not to worry about cancer coming back. This is very common if you’ve had cancer.

For other people, colorectal cancer may never go away completely. Some people may get regular treatment with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or other treatments to try to control the cancer for as long as possible. Learning to live with cancer that does not go away can be difficult and very stressful.

Ask your doctor for a survivorship care plan

Talk with your doctor about developing a survivorship care plan for you. This plan might include:

. A suggested schedule for follow-up exams and tests

. A list of possible late- or long-term side effects from your treatment, including what to watch for and when you should contact your doctor

. A schedule for other tests you might need in the future, such as early detection (screening) tests for other types of cancer

. Suggestions for things you can do that might improve your health, including possibly lowering your chances of the cancer coming back, such as diet and physical activity changes

. Reminders to keep your appointments with your primary care provider (PCP) who will monitor your general health care, including your cancer screening tests.

What’s the survival rate for people with colorectal cancer?

Having a colorectal cancer diagnosis can be worrying, but this type of cancer is extremely treatable, especially when caught early.

The 5-year survival rate for all stages of colon cancer is estimated to be 63 percent based on data from 2009 to 2015. For rectal cancer, the 5-year survival rate is 67 percent.

The 5-year survival rate reflects the percentage of people who survived at least 5 years after diagnosis.

Treatment measures have also come a long way for more advanced cases of colon cancer.

According to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, in 2015, the average survival time for stage 4 colon cancer was around 30 months. In the 1990s, the average was 6 to 8 months.

At the same time, doctors are now seeing colorectal cancer in younger people. Some of this may be due to unhealthy lifestyle choices.

According to the ACS, while colorectal cancer deaths declined in older adults, deaths in people younger than 50 years old increased between 2008 and 2017.

Managing long-term side effects

Most side effects go away after treatment ends, but some may continue and need special care to manage. For example, if you have a colostomy or ileostomy, you may worry about doing everyday activities. Whether your ostomy is temporary or permanent, a health care professional trained to help people with colostomies and ileostomies (called an enterostomal therapist) can teach you how to care for it.

Some people with colon or rectal cancer may have long lasting trouble with chronic diarrhea, going to the bathroom frequently, or not being able to hold their stool. Some may also have problems with numbness or tingling in their fingers and toes (peripheral neuropathy) from chemo they received.

If the cancer comes back

If the cancer does recur at some point, your treatment options will depend on where the cancer is, what treatments you’ve had before, and your overall health.

Could I get a second cancer after colorectal cancer treatment?

People who’ve had colorectal cancer can still get other cancers, In fact, colorectal cancer survivors are at higher risk for getting another colorectal cancer, as well as some other types of cancer.